The many worlds of Schrödinger's cat

It started as a thought experiment to bring to light an apparent paradox of quantum mechanics, but the many-worlds interpretation sheds a different light on Schrödinger’s cat. In a real sense—if you’re willing to accept the premise of many worlds—Schrödinger’s cat can be both alive and dead at the same time. The wave function never collapses: what we see as collapse is only an illusion, brought on by entanglement between the observer, the observee, and the rest of the environment, as the universe diverges to realize all possible measurement outcomes simultaneously.

It’s a framework that has profound implications for the true nature of reality. Although it may be difficult or impossible to find direct evidence for many worlds, the interpretation is worth considering because it does away with wave function collapse and the arbitrary separation between the “microscopic” and the “macroscopic” that exists in the Copenhagen interpretation, while still remaining consistent with observations.

As cosmology flirts with the possibility of a spatially infinite universe, many worlds lets us consider an infinite number of universes. In the multiverse, what does it mean that every quantum measurement that can happen, does happen? What does it mean to be “you” when “you” are constantly diverging into separate entities who can never interact with each other, and each of whom is convinced that they are the only version of themselves that really exists?

But let’s consider a more modest question.

Enter Superposition

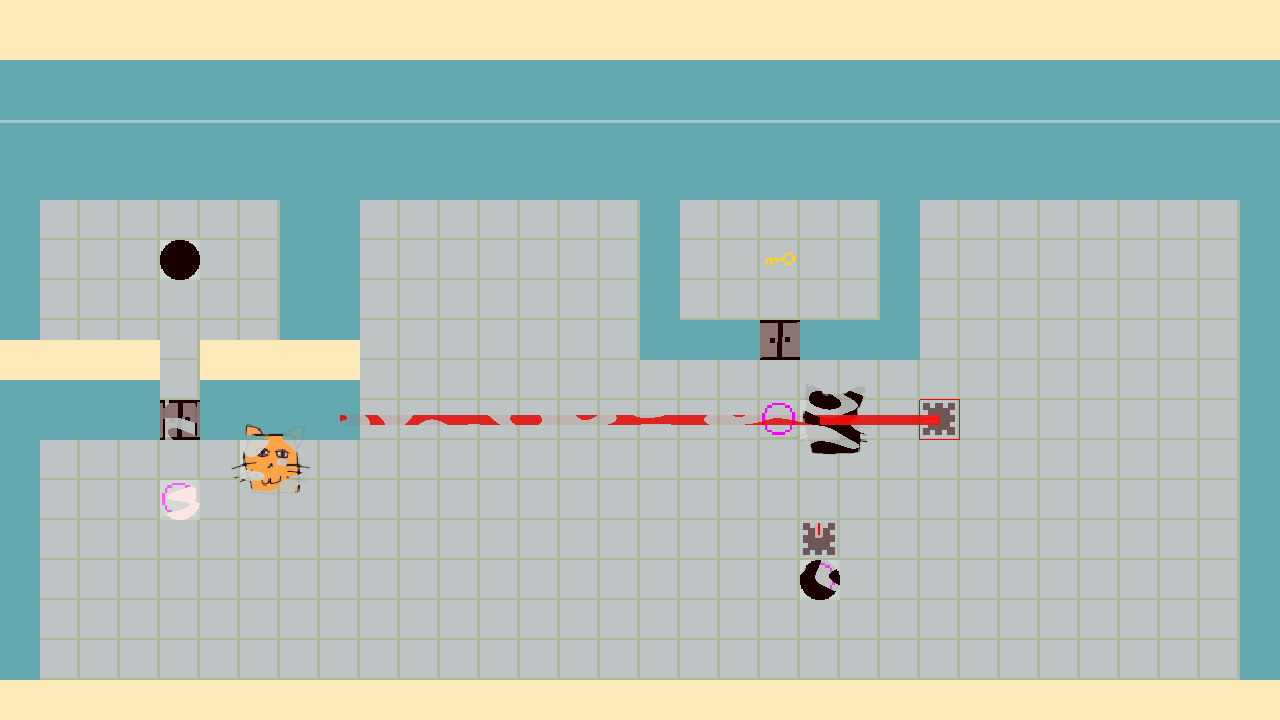

Superposition is a video game that I’m making with my friend Rory Soiffer. The premise is: You are Schrödinger’s cat, and you really can be in a superposition of alive and dead.

It’s a puzzle game, but we wanted to make it approachable and more like a 2D action-adventure game than a pure abstract puzzle game would be. The player directly controls Schrödinger’s cat, and in real time instead of with discrete turns. But under the hood, a quantum system is being simulated. Like the thought experiment, Schrödinger’s cat gives us a bridge between the microscopic and the macroscopic—between the weird quantum world and the familiar classical world.

An important point of clarification: I’m using the many-worlds interpretation as a metaphor for the game’s mechanics, since Rory and I decided to call our representation of superposition states in the game “universes” that are part of a “multiverse.” But they are not the same thing as MWI. Universes in the game can be “recombined” even if different events happened in their history, unlike MWI. Superposition actually doesn’t assume any particular interpretation of quantum mechanics—we forbid measurement for simplicity.

The good news is that Superposition does actually model a mathematically accurate quantum system. Actually, the “universes” are just a fancy name for basis states and their corresponding probability amplitudes, and the “multiverse” is just the complete state of the system. When universes recombine, it is due to the interference of basis states, just like real quantum mechanics.

So with that said, the question is: How do we design a video game that’s fun to play while being mathematically rigorous and consistent with quantum mechanics?

Let’s define our Hilbert space.

State space

The Hilbert space, which is really just the space of possible states that our game can be in, is the product of the states that each entity in the game can be in. As of the time of writing, we just have two entities that have quantum state: Schrödinger’s cat, controlled by the player, and quballs, which are ball-shaped qubits that can be picked up and moved around the level.

By “quantum state,” I mean that the state is a linear combination of basis states in \mathbb{C}^n, where the coefficient on each basis state is the probability amplitude, and the squared magnitudes of the probability amplitudes must sum to one. Each level contains a discrete grid, and each entity can be in one or more of these cells. That is, each cell is a basis state, and an entity is in a linear combination of them. This is in contrast with other state in the game that is not quantum, which we call metadata. For example, the precise pixel position of each entity is part of the game state, but not the quantum state. We use the precise position to smoothly animate objects across the grid, but it does not affect the behavior of the quantum system. A quantum gate is applied equally to every object in a cell, regardless of if it is in the center or one of the corners.

So here is a complete list of the quantum state for our two types of entities:

| Player | Quball |

|---|---|

| Current position | Current position |

| Alive or dead | On or off |

| - | Carried or not carried |

And that’s it, at least in terms of basic entity types. Naturally, if there is more than one quball in the level, the state space expands.

There are other kinds of objects like doors that can be either open or closed depending on the quball that is placed next to them, but the doors do not actually hold quantum state. They simply reflect the state of the quball that is affecting them. Quantum gates cannot be applied to the doors themselves, so they are not listed here.

You may notice that alive-dead, on-off, and carried-not-carried sound like qubits, but position is more complicated. Position is a qudit that depends on the size of the level; it increases the size of the state space dramatically compared to just having a few qubits lying around. And position is treated equally to the binary state of qubits. Just as a quball can be in a superposition of on and off, it can be in a superposition of here and there. There are more basis states for position, so there are more possibilites for superposition states as well.

Gates

We need quantum gates to evolve the state of the system over time. We define a gate as two functions:

trait Gate[A] {

def apply(value: A)(universe: Universe): NonEmptyList[Universe]

def adjoint: Gate[A]

}adjoint is familiar if you know some quantum computing. It is the gate that does the reverse of the original gate when given the same argument.

apply takes an arbitrary argument to give to the gate, and a universe in which to apply the gate. In return, the gate gives you one or more universes back. The meaning of the first parameter value depends on the specific gate used. Usually, it contains the ID of the qudit whose state should be changed and any additional parameters that the gate needs, such as the degree of a rotation.

Remember, when you see “universe,” just think of a term in an equation representing a quantum state: a probability amplitude multipled by a basis state. In traditional quantum mechanics, we can describe the state of a two-qubit system as \ket{\psi} = a\ket{00} + b\ket{01} + c\ket{10} + d\ket{11}. Here, we instead say that we have four universes \ket{\psi} = \{U_a, U_b, U_c, U_d\}, where m_\alpha represents additional metadata for U_\alpha that I have omitted:

\begin{aligned} U_a &= \big(a, \{ q_0 \to 0, q_1 \to 0 \}, m_a\big) \\ U_b &= \big(b, \{ q_0 \to 1, q_1 \to 0 \}, m_b\big) \\ U_c &= \big(c, \{ q_0 \to 0, q_1 \to 1 \}, m_c\big) \\ U_d &= \big(d, \{ q_0 \to 1, q_1 \to 1 \}, m_d\big) \end{aligned}

Then apply just maps a universe (term) to one or more universes (terms). For example, let

\begin{aligned} U_0 &= \big(a, \{ q_0 \to 0 \}, m\big) \\ U_1 &= \big(a, \{ q_0 \to 1 \}, m\big) \end{aligned}

where the only difference between U_0 and U_1 is the state of q_0; their amplitudes and metadata are identical. Define division of a universe U = (a, s, m) with amplitude a \in \mathbb{C}, state s, and metadata m by some constant c \in \mathbb{C} as

\frac{U}{c} = \left(\frac{a}{c}, s, m\right)

Then the gates X and H would map

\begin{aligned} X(q_0, U_0) &= \left\{ U_1 \right\} \\ X(q_0, U_1) &= \left\{ U_0 \right\} \\ H(q_0, U_0) &= \left\{ \frac{U_0}{\sqrt{2}}, \frac{U_1}{\sqrt{2}} \right\} \\ H(q_0, U_1) &= \left\{ \frac{U_0}{\sqrt{2}}, -\frac{U_1}{\sqrt{2}} \right\} \\ \end{aligned}

which should look familiar. For example, compare to the traditional H \ket{1} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{0} - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{1}.

We go to the trouble of calling terms universes because we want to provide the illusion that each term represents an entire world, with its own processes and animations in the game, where all of the qudits have a particular classical state. To do this we need to associate more information with each term than just its probability amplitude and basis state, such as precise pixel positions on screen and animation timers. That’s why we don’t use the traditional matrix-vector representation of operators and states.

Gates are the only way to change the state of the quantum system in Superposition. How does the player pick up a quball? By applying the X gate to qubit representing the quball’s carried state. How does the player move? By applying the \mathrm{Translate} gate to the qudit representing their position.

Transformations

Gates are functions, so they can be transformed like functions. An example is contramap which transforms the type of the input value to a gate. Its type is:

def contramap[A, B](f: B => A)(gate: Gate[A]): Gate[B]This is called contramap instead of map because the order of the types is reversed relative to map. The new Gate[B] applies the mapping function on its input of type B to transform it into type A, and only then can it call Gate[A]. If you’re into Haskell, gates are actually contravariant functors.

Another example is multi, which takes a gate that operates on a single value of type A and creates a gate that operates a sequence of those values and accumulates the universes:

def multi(gate: Gate[A]) = new Gate[Seq[A]] {

override def apply(values: Seq[A])(universe: Universe) = values match {

case Nil => NonEmptyList(universe)

case x :: xs => gate(x)(universe) flatMap gate.multi(xs)

}

override def adjoint = gate.adjoint.multi contramap (_.reverse)

}Basically: if the sequence is empty, return the original universe unchanged. Otherwise, apply the first value to the gate in the initial universe, and then repeat for the remaining values using the universes produced by the first application. This is analogous to the ApplyToEach operation in Q#.

A more complicated transformation is something we call controlled, whose name is somewhat misleading if you’re used to the traditional meaning of a controlled operation:

def controlled[A, B](f: B => Universe => A)(gate: Gate[A]) = new Gate[B] {

override def apply(value: B)(universe: Universe) =

gate(f(value)(universe))(universe)

override def adjoint = gate.adjoint controlled f

}Looking at the type, controlled: (B => Universe => A) => Gate[A] => Gate[B], you can see that it is identical to contramap: (B => A) => Gate[A] => Gate[B] except the mapping function also takes a universe. This difference in types is a complete description of the difference in the behavior of controlled and contramap: the only difference is that with controlled, you can change the value applied to the gate based on the state of each universe.

This is perhaps most useful when composed with multi. If you apply multi and then controlled, you can inspect the state of the universe and return Seq(value) if some condition is satisfied, which indicates applying the gate normally, or Nil if the condition is not satisfied, which indicates not applying the gate (or applying the gate to no values). This behavior is analogous to traditional controlled operations in quantum computing; the controlled function is just more general.

Unitarity

All gates must be unitary, which ensures that any change to the game state is sound. No matter what action the player takes, there must be a way to reverse it so that the system is in the same state it was before the action was taken.

The reverse, or adjoint, of each gate is pretty obvious, and not that exciting. The adjoint of X(q) is X(q). The adjoint of \mathrm{Translate}(q, dx, dy) is \mathrm{Translate}(q, -dx, -dy).

But unitarity also imposes some restrictions on the player’s abilities that make the game more interesting and challenging.

For example, let’s say there are two quballs. You’re carrying one of them, and the other one is on the floor. You want to drop the one you’re carrying on top of the other one, without picking the other one up. You can’t just reset the carried qubit of the quball you’re carrying—that requires measurement. You have to use an X gate, but any control you use will target both quballs, because they share everything in common except for their carried state, and you can’t control on a quball’s carried state while also targeting its carried state with the same gate. This means that you have to pick up the quball on the floor when you drop the quball you’re carrying.

Another example is if you are in multiple places at the same time—a superposition of position. When the player moves, all copies of them move in the same direction simultaneously. This means that all copies must keep the same relative position; if moving in a direction would cause any copy to hit a wall, then none of them can move in that direction. If they could, then either you could walk through walls or move your copies closer together. The former would make some puzzles trivially easy and the latter would violate unitarity.

This isn’t to say that these things are impossible. You just need to be a little more creative and use gate controls to your advantage. For example, player movement is automatically controlled on the player being alive—naturally, you can’t move if you’re dead. If one version of you is dead and the other version is alive, you actually can change their relative positions in a way that’s unitary.

Puzzles

We designed Superposition’s game mechanics so that we could make puzzles based on real quantum circuits and algorithms. Of course, the hard part now is in actually designing enough fun and interesting puzzles to make a complete game.

Our first real level was a kind of entanglement circuit. You start with a \mathrm{CNOT} gate, an X gate, a quball in the \ket{+} state, and another quball in the \ket{0} state behind a locked door. To finish the level, you need the reach the goal which is behind another locked door.

I won’t spoil the solution, but I’ll give a hint. Doors are unlocked by quballs in the on state, and if a quball is in a superposition of on and off, the door is also in a superposition of unlocked and locked. But because movement is unitary, you can’t just have one version of the player walk through the open door while the other player stays behind—both need to move in tandem. So a whole cat and a half-open door is no good. But if you entangle the cat with the quball that is in superposition, so that the alive cat is correlated with the on quball and the dead cat is correlated with the off quball, then you can walk through.

We’re planning to design more puzzles like this one but with increasing difficulty and circuit complexity, using more advanced gates and algorithms. If you’re interested in getting involved with this or any other aspect of game design, like artwork, graphics, or sound, feel free to get in touch or pick up a task!